Rebecca Brooks Harvey

|

| Rebecca Brooks Harvey. Image courtesy of the Kansas Collection, Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas Libraries, Lawrence |

|

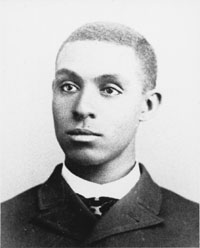

| Sherman Harvey, son of David and Rebecca Brooks Harvey, graduated from the University of Kansas in 1889. He worked as a Lawrence school teacher and principal and later as Douglas County Clerk. After serving with his brother Frederick, a physician, in the Twenty-third Kansas Regiment, an all-black unit in the Spanish American War, he studied law at the University of Kansas. Although he did not finish

his law degree, he passed the Kansas bar examination. In l902 he moved to the Philippines, where he practiced law for nineteen years before returning to the United States. Image courtesy of the Kansas Collection, Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas Libraries, Lawrence. |

|

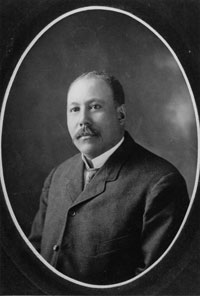

| Dr Frederick Grant Harvey, a younger brother of Sherman Harvey, took work leading to a course in medicine. Because Kansas at that time had no school of medicine, he went on to the Mehary Medical School in Nashville, Tennessee. He practiced first in Wyandotte County for a time and at last returned to Lawrence. Along with his brother Sherman, he served in the Twenty-third Kansas Regiment, an all-black unit in the Spanish American War, as assistant surgeon. After the war he was, for the rest of his life, a well-known figure in Lawrence. Image courtesy of the Kansas Collection, Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas Libraries, Lawrence. |

by Edward S. Harvey

edited by Margaret Lynn

The life of Rebecca Brooks—who was at first neither Rebecca nor Brooks—began in dimness and un-expectation. She herself in later years could not tell the time or the place of her birth nor the name of the parents to whom she came. In some far southern state she was born, the child of slaves, the possession not of them but of their master. The triumph of her life is that with her years she passed from this namelessness and emptiness, to dignity and respect and prosperity. She moved from a cloudy obscurity to an identity of her own, in light and openness. And the most that she and her husband achieved was based on what they were in themselves.

She was born the chattel of some now unknown master, apparently of little station, for he soon passed the child on to pay some casual debt. In her later years she could not raise one circumstance of her infancy to tell to her own children. At the home of her new owner the baby was put into the hands of a slave-woman to be cared for. This foster-mother named her Rebecca and added her own surname, Brooks. Rebecca Brooks she became, and at least she had a name. When the child was five or six years old the master brought her and the slave-women from this vague place in the deep South—overland, of course—through South Carolina and Georgia and Alabama, and by boat from Mobile to New Orleans, and again by boat up the rivers to Little Rock. At Van Buren, Arkansas, the child was sold to a planter named Foster, on whose place she grew to womanhood. Here she knew and in time married, young David Harvey.

There is nothing kind to say of slavery in any aspect. But apparently the Harveys were not subjected to the worst of it. Evidently in later years Rebecca Harvey did not carry the bitterest possible recollections from her early life, or detail them to her children. David's father, Allen Harvey, was overseer of the Foster plantation, and David himself was a teamster. Foster would send the young man off into Indian Territory, with mule teams, and loads of produce to market. He sent him with all confidence that David would come back and bring teams and wagons, and money for the goods he had sold. It would seem then the young couple did not feel the harshest humiliation of their condition. But their first child was born a slave.

What the Civil War did to the circumstances of the Foster plantation, one does not know. Much fighting went on in the region about Van Buren and Fort Smith and the section must have been affected by the circumstances. Arkansas had seceded from the Union, but it had large numbers of federal sympathizers and in the battles of upper Arkansas the North was generally successful. But one result of the local war was to separate husband and wife for a time. Somehow, in circumstances not now clear, David went with a federal force up to St. Louis and then on to Leavenworth. This was at some time near the end of the war.

One can conceive the anxiety of these days for both husband and wife, each ignorant of the place or condition of the other. Slavery had dealt very casually with the marriages of Negroes, and both of them knew tragic stories of the cruel separation of families. David and Rebecca had no assurance that they would be together again, or when or how. And each was in this time undergoing the privations of the period.

The Emancipation Proclamation came, announcing freedom to those who had been enslaved and a new life for them. Even now we feel a thrill at the mention of it and its correction of a great wrong. But who cinsiders the mixed feelings with which the slaves learned of it, or what anxiety must often have gone with this new freedom? They wee free, or would be when the North won the war, but penniless and homeless—unowned but unowning. They had been workers on the land but they possessed not a foot of land; they had cared for houses but they had no houses of their own. Their former masters were now too poor to hire them. It is a story which has never yet been fully written—or perhaps fully felt by readers.

For Rebecca Harvey a kind of solution came when in 1863 General Blunt, who before the War had been with the anit-slavery party in Kansas and had been one to assist in the escape of slaves through the Territory, gathered up a body of ex-slaves and had them conducted up to Kansas. His action was precipitate and unauthorized, but his party of refugees, with many hardships on the way, did reach its destination. They came to what was known as Miller's Grove, a few miles east of Lawrence. Penniless and unprovided-for, they seemed to have reached a dubious haven. But for one woman among them it proved to be the right place to choose. Since up in Leavenworth David Harvey heard of the arrival of the company from Arkansas, and came to Lawrence to see them. Thus he found his wife and little son.

The Kansans of the Sixties were not rich, and the War had not made them richer, but the refugees were chiefly absorbed among the settlers, as helpers in the village or workers on the new farms. A couple of such evident integrity and capability as the Harveys soon found emmployment. They made friends also, in a community actively sympathetic with slaves and pre-disposed to be helpful to them. The Kansans themselves had suffered much for the cause of Abolition and—were now ready to prove the sincerity of their declarations. So Rebecca and David found kindness and neighborliness at hand. To this they responded in a way to show their own deserving.

In the spring of 1864 they were able to rent a few acres of the land of Stephen A. Ogden, then sheriff of Douglas County. The rent was paid from the crops. In succeeding years they did the same. Thus they went on, working and saving. Most people in the world—at least most heads of families—have a longing to own land, to connect wome piece of earth with themselves. A man feels richer when his name goes with some stretch of acres. One may imagine the pride and deep feeling with which the Harveys acquired their first piece of ground—fifteen acres—their own, to bring forth their own crops. Five years of hard work and then a deed which meant a farm, and a home in their own name. Then followed more work, decent intelligent work, and successive additions of land. In the end the Harvey estate, now the farm of the youngest son, included nearly half a section of acreage.

While continued labor brought the Harveys greater comfort and prosperity, they were taking their place among the affairs of the settlement about them—in school matters, in the country church, in the simple neighborliness of the Blue Mound section. All of Douglas County was forward-looking in those days, hoping that the new state was to be a good state, bringing to its pioneer problems whatever acquisition of method or knowledge came its way. In all this the Harveys had part, and in the simple customs of those primitive times; they grew in farming skill as others grew, and in profit as well. They took part in neighborhood helps and needs. Rebecca was widely known as nurse and midwife, and David also came in to help in sickness or in some stress of hard work or need of special skill. The new settlement was growning and improving, and in all its improvement there was advantage for the Harveys. They knew year by year the happiness of owning, the happiness of home-making, the deep satisfaction of being regarded as neighbors and as citizens.

As their lives opened out they took to themselves all the opportunities which this new land was developing. They had the intelligence to see what chances were at hand and to recognize their usefulness for themselves. When the little University attained to a second building—now a large building—and laid the corner-stone of Fraser Hall in a public occasion, the Harveys attended the ceremony and the basket-dinner which followed it. They listened to talk about education, to the aspirations of the state, its ambitions for its children. They went away from the Hill saying, "We will send our sons to the University." As the state had become their state, this was to be their University.

So it was to be carried out. The greatest happiness for Rebecca and David—beyond the satisfaction of prosperity and citizenship—must have come from the character and success of their children. There were four in all, four sons. The oldest was the one born in slavery in Arkansas; the other three were born on Blue Mound. The oldest one, William, took training in a business college but later returned to his father's home, where he died while still a young man. The other three, as Rebecca and David had promised each other, all entered the University of Kansas, all took degrees, and each, incidentally, earned a K by participation in athletics.

The oldest of the three, Sherman, took his Bachelor of Arts degree in1889. He taught for several years in the Lawrence schools, was Clerk of the District Court for two years, enlisted for service in the Spanish-American War. He as Captain of Company B in the Twenty-third Kansas Regiment. After his discharge he re-entered the University, took a degree in Law ans was admitted to the Bar. He then went to the Phillippines where for nearly twenty years he practised law and engaged in business. On his return to the States he spent his remaining years in a Veteran's Hospital.

The second brother, Grant, in the University took work leading to a course in medicine. Kansas at that time had no School of Medicine and he went on to the Mehary Medical School in Nashville, Tennessee. He practised first in Wyandotte County for a time and at last returned to Lawrence. He also was with the Twenty-third Kansas Regiment, as Assistant Surgeon. After the war he was, for the rest of his life, a well-known figure in Lawrence, a man of character and great usefulness. He was a leader among his own people, helpful with advice and plan, a kind of liaison volunteer between the two races.

Edward, the youngest son, two years ago was one of the University alumni to be awarded the fifty-year gold pin, at Commencement. He holds the Bachelor of Arts degree and like his brothers was distinguished in athletics while an undergraduate. After college he for a time held a clerical position in Washington, under Congressman J. D. Bowersock. He returned however to his home and to what was to be and is now, his home. He has become that important person, a good citizen, full of public duties, and a good farmer. In these days an intelligent and public-spirited farmer wins distinction. On his farm Ed Harvey had developed fine lines of stock and of corn, and has been an intelligent student of current themes in agriculture.

He has also made time to take on many civic or social positions and duties. In offices in the country church, on the local school board, on juries, as justice of the peace, as officer in the Grange, as secretary for many years to the Farmers' Instituet, as president of the Farm Bureau, he has been an important and useful man and widely-known citizen. At his farm, on the slopes of Blue Mound, the fifth generation of Harveys is now at home; for David, when well-established there, had sent to bring his father from Arkansas, that he might spend his last years with the family; and Edward Harvey now had grandchildren growing up on the place.

Rebecca Harvey could scarcely have had greater satisfaction or higher fulfillment of hope, than in spending the end of her life thus on her own estate, the land which she and David had earned, and in having at hand her sons, known and independent, useful and respected. She must have been aware too that they had become so through following the wise and upright teachings of David and herself.

Rebecca had traveled a long way in the years of her life. It is appropriate that her picture should now be on the wall of the Lawrence Room in the University Library, among those of other pioneers, makers of Kansas through stability and integrity and generous purpose.

Reprinted with permission of the Kansas Collection, University of Kansas Libraries