The Promoters —

Lawrence's All-Black High School Basketball Team 1920s-1950

From the 1920s to 1950 Lawrence, Kansas, had an all-black high school basketball team called the Promoters. This team won its league championship twice and tied for first place twice. The Promoters had its own pep club, the Red Peppers, and three female cheerleaders. When the high school basketball team was integrated in 1950, the Promoters disbanded.

From the 1920s to 1950 Lawrence, Kansas, had an all-black high school basketball team called the Promoters. This team won its league championship twice and tied for first place twice. The Promoters had its own pep club, the Red Peppers, and three female cheerleaders. When the high school basketball team was integrated in 1950, the Promoters disbanded.

In the highly segregated society of the time it wasn't easy for the Promoters to even exist. The high school would not allow the team to use its basketballs or to practice during the day. The team had to ride the Lawrence Rapid Transit to play in Kansas City and because team members couldn't be served in restaurants they had to eat in the homes of opponent's parents.

That the team managed to exist for nearly thirty years shows the fortitude and creativity of its African American team members as well as the support by its black and white coaches. The team succeeded and excelled despite racial discrimination and segregation. The Promoters' history is an example of interracial goodwill and commitment to providing blacks opportunities to shine in the sports world.

In 2005 Alice Fowler and Amber Reagan-Kendrick of the African American Families Oral History project interviewed former Promoters players, Charles E. Newman, Verner Newman III, James Barnes, Leonard Monroe and William Moore. This oral history project was made possible by a grant from Capitol Federal Foundation.

See also "Champions! " Copyright Sunflower Publishing

LAWRENCE/DOUGLAS COUNTY

PROMOTERS BASKET BALL TEAM:

Charles E. Newman, Verner Newman, III, James O. Barnes, Leonard Monroe, William Moore

Interviewed by Alice Fowler and Amber Reagan-Kendrick

April 8, 2005

AMBER: Today is April 8, 2005. We're at First Regular Church in Lawrence, Kansas, and we're interviewing the Promoters here. And we are going to begin with Mr. Charles Newman.

MR. CHARLES NEWMAN: Hello. I'm Charles E. Newman from Lawrence, Kansas, and I'm not sure what you want (laughter).

AMBER: (Laughter) That's okay.

ALICE: That's okay.

AMBER: Newman number two.

ALICE: Verner

MR. VERNER NEWMAN: Verner Newman the third. I went out for basketball for Promoters when I was in ninth grade. They wouldn't let blacks play at the high school. We had the opportunity to play at the junior high school, so they would let us go down there and play, but I was only four foot nine, so I didn't play not one minute, not one second (laughter). So, Bruce the teacher, was a basketball coach, and he said if I grew any, he would make sure that I got a suit the next year. So I don't know what happened, but that following summer I went from four foot nine to five foot ten and a half, and I got a suit. So I actually started playing in '46, '47 and '48.

We played against all-black teams. We played against Leavenworth, Topeka, St. Joe, Baldwin High, Missouri, Archie Coles in Kansas City, Missouri, and Northeast Junior College in Kansas City, Kansas. If you're wondering why we played a junior college, there wasn't anybody in the state of Kansas that could beat Sumner playing basketball in high school. So no one played Sumner. Sumner played Missouri and Chicago and Oklahoma City and St. Louis, and so we played Northeast Junior College, and we couldn't beat them (laughter). One year they had a kid that wasn't a senior, he was fourteen years old. He had three kids who were six foot five.

But we did get to travel out of state. I got to go Missouri, but like the schools in this part of the country--Northeast Kansas City and Lawrence High, they couldn't go out of state. They had a state law, unless you lived on the border, like the Oklahoma border or in Western Kansas, you played Colorado or Oklahoma, but you couldn't here. But we got to go. We used to go to Barlett and Atchison. We'd always make sure one of the parents would feed us. We'd go to their house and go down in the basement, and they had meals for us. That's where we would eat, in the parents' houses. One lady had a dance for us. I'll never forget, they had opened the door and that song "Richard" came out, and all these girls were asking us which one of us was named Richard. So we weren't smart enough to tell them our names were Richard (laughter). I kept pointing to Bud Monroe. He was a driver, and kept pointing, "Him, him, him, him, him, him." Thank goodness we did, because he ended getting married to one of them (laughter).

I played '46, '47 and '48. And right after our last game in '46 we were proud of that, and we to our basketball coach, Scotty Barnes, and told him we wanted to play football. And so he said, "Well, I can talk to the principal." He went and saw Mr. Worthy, and Mr. Worthy said, I'll make some calls." So he made one telephone call to the Shawnee Mission Rural High School principal. It wasn't Shawnee Mission North or East or West at that time. It's Shawnee Mission North now, but they used to call it Shawnee Mission Rural. Anyway, the principal there said, "I'm really glad that somebody broke that up." He said, "I always wanted to." He seemed pretty glad, so he said, "I'll take it from here." He said, "I'll make the rest of the calls." About 3:00 that afternoon in Northeast Kansas, the league was integrated for football. So the next fall of 1947, we all got to go out for football for the first time. But, unfortunately, they didn't integrate basketball until 1950. Like I said, it was just getting to be too close (laughter). That's my history with them. I had my uncle's history, Jesse, he played on one of the first basketball teams. I don't know how he wanted to do his, but I do have it.

ALICE: We'll do his after we do everybody today, or stop in maybe. How's that?

MR. VERNER NEWMAN: Okay.

MR. VERNER NEWMAN: I played with the Promoters. I started out in 1940. Of course, a lot of the guys that I played with were getting ready to go into World War II. So a lot of them wasn't anxious to really leave the school,l because they knew they'd have to go to the military. And so I played in '42, '43 and '44. And it was like my nephew said. We could play if you was in the ninth grade in junior high, you could go to the high school and play with the Promoters and at Lawrence High. I went to school with a lot of very interesting people at that time. I went to school with one of the governors, Governor Bob Docking, and some of the others. On Saturdays, we used to slip in at the Robinson Gymnasium. We'd go up there and play basketball. Because at that time, KU played at the Hoch Auditorium on the stage. And Phog Allen would come in and the guards would come in and say, "Well, it's time for you guys to leave," and we'd have to leave. And it was quite an interesting thing. But I was really glad to play basketball, just like Archie Coles. And some of the guys like Archie Coles, they went on to play with the Globetrotters. But one thing that I will always remember, when I graduated in 1944, May, I went up and got my diploma and I came home, and there was a letter there for me and Uncle Sam saying, "Greetings" (laughter). And that was on May 29, and I was to report to the draft board June 8th. And on June 8th I was on my way to the Navy and I was in there for two years. So I hadn't resented it because I had some interesting things. I played with a lot of people that went on to the big times, pro football and stuff like that. But I didn't regret it. And so that's about it.

MR. MOORE: My name is William Moore, and I went to Lawrence High and played with Promoters in 1934, '35, '36 and '37. At that time we had a white coach, Forrest Nall, and outside of that, everything was all black. We weren't allowed to play football. We were allowed to go out for track, but basketball was a sport that we had more problems getting in. I believe that at this point I'm about the oldest Promoter that is still living. Wilbur Whiteside I think is still living, and he was a Promoter that played along with me.

I went into the service in 1942, I believe it was, and served three years in the Army engineers. I came home and went to work at the paper mill there in Lawrence. I don't know whether there are any of you who probably remember Arthur Johnson. We all got together and built the softball field there at Woodlawn School. And I lived right across from Woodlawn school, but when it come time to go to school, I had to walk a block and a half to an all-black school. It was the only all-black school at that time in Lawrence that wasn't integrated. All of the rest of the schools were integrated and that was my experience as a Promoter.

MR. BARNES: I'm James O., middle initial, Barnes. And Brother Moore here spoke about Lincoln School, so I want to get this in. I and Charles Newman, who spoke first on this tape, and Alice Fowler, who is on the committee, started kindergarten together in 1939 at Lincoln School. There were all three of us anyway. We're still here (laughter).

MR. BARNES: And it's like they had said earlier, when I was in the ninth grade in 1949, myself and Charles Newman, Frank Willingham, and Phillip White started playing on the Promoters. But we played on the Promoters' 'B' Team. We didn't play on the 'A' Team at that time, because in 1950 there was no more Promoters. They integrated basketball, and the blacks could play on the Lawrence Lions' team in 1950. And I didn't go out for basketball in 1950. I don't think I was good enough for that team anyway, so that didn't bother me (laughter). And Walter Mumford and I were the only two players out of North Lawrence on that 1949 team, because we used to walk from the practice out at the high school across that cold bridge in the winter time, going to North Lawrence, when we couldn't get a ride from Northern Ball up to the Community Building when the city league was playing. We played on either the Woody's Aces or the Green Gable. I don't remember exactly which one.. That's about all that I can remember about the Promoters at that time.

MR. MONROE: I'm Leonard Monroe, and I played on the Promoters '48 to '49, and I actually really enjoyed that. We never had a bus or anything like that to take us anywhere, so we had two, what might call designated drivers that took us everywhere we went. One was my brother, Waldo "Bud" Monroe, and there was Dean Harvey. So they always took us to all of our games. Then we'd come back. Of course, we couldn't eat in none of those places downtown, but sometimes we'd go down to the Green Gable and get something eat or the Blues Bucket Shop and get something to eat. But I really enjoyed those years, because we couldn't do anything else but that. Anyway now, we were playing football and track. That was my specialty as far as I'm concerned, was track, because I had a cartilage knocked loose in my knee in football, so I never really got to play football that much. But track and the Promoters were my forte. And when they integrated in 1950, I was one of the first Black Lions, you might say. But, because of my knee operation that September, it was nowhere in shape to really play basketball. So I more or less quit the team. We had what we called a city league back then also. So I joined the city league. We were the Michigan Wolverines. We were the Wolverines in the city league, which we won the championship in 1950. I'll never forget that because we enjoyed beating Rex Johnson's team.

But anyway, but track was my main specialty. And I kept telling the coach I was going to KU to run track. But the coaches, my history teacher, Leonard Haustra and my other two coaches, Guy Barnes and Doc Watson said, "Well, why don't you go to K-State or Emporia State or Washburn?" I said, "No, I'm going to KU. They have the best track team in the world." Which they did have at that time. But I never knew why they kept trying to tell me to get into one of those schools. But I went on and started KU. When it come time to go out for track, I went out for track and went down to the stadium to go out and get on the team. And that's when Bill Eason said to me, "I'll never run track for him." Although I was second fastest quarter miler in the state of Kansas, he wouldn't give me a uniform. So I dropped out of KU and joined the Air Force. And that's my history up to that time until I went into the military.

AMBER: I just have one question before we continue. Now, all of you said that Promoters ended in 1950, that was the last...?

MR. MONROE: Forty-nine.

ALICE: Oh, '49? Okay. So what year did the Promoters begin?

MR. BARNES: I have one interview my uncle, Jesse Newman, Senior. He says, "He will never forget the White Shadow." And said, "The Promoters, an all-black high school basketball team from the 1920s to 1950, traveled throughout the region and won at least two league championships." "If hadn't been for the White Shadow," Newman said, "Lawrence's black Liberty Memorial High School students would not have been able to play basketball in the early 1930s. Without the White Shadow, the Promoters Basketball Team would have disbanded, and Newman' nephew, Verner, would not have had a team to play on fifteen years later. Horace Nall was the White Shadow, a nickname he earned as a white junior high school teacher who coached the Promoters, a Lawrence black basketball team." "There wasn't any black teachers," Newman said. There wouldn't have been a team had it not been for him. He was a God-send as far as I'm concerned." "Nall, being a young athletics teacher, put in his own time and money to make sure all the Lawrence youth had a chance to play basketball. This white junior high school teacher took it upon himself to buy eight suits for eight boys," Newman said. "He paid the fifty dollar fee to enter the team in the all-black league. He said he never understood why a white teacher would coach the team. But I didn't find out until the war broke out in 1941. And I found out then that he was one of the Army's chaplains. He had that much religion that caused him to do that much for black folks in Lawrence." Nall took over the team in 1928 or 1929. He was not sure when the Promoters were first organized. Liberty Memorial High School yearbook contains references to the team dating to at least 1926. He remembers that black Kansas University students, such as a Doxie Wilkerson, coached the team before Nall." That's W-I-L-K-E-R-S-O-N, first name Doxie, D like dog, -O-X-I-E. "But the Black Allegiance didn't stay long in Lawrence. It was kind of a rough time graduating from KU. You had to go south to teach school." It said, "Newman to went high school in 1929, he began to substitute on the team. He became the starting center in 1930. That year the Promoters played in the Missouri Valley Invitational Athletic Association, winning the conference tournament, placing third in the league." The thing about it, there wasn't enough black high school students to make a team, so they had to reach into the junior high school to get players. "Living by the rules," as Newman recalls, "it wasn't easy for the team to even exist. The high school wouldn't allow the black players to use its basketballs. Promoters couldn't wear a Large 'L' on their game jerseys like the white teams. Prospects were bleak in Lawrence for anyone who was not white. The Promoters offered one of the few opportunities for black youth to play. The team traveled around Kansas and Missouri, playing other black teams. They played at St. Joseph, Kansas City, Missouri, Kansas City, Kansas, Topeka, Ottawa and Leavenworth."

The team couldn't practice during a regular school day. Most practices we had at the high school at night, two hours from 7 to 9 p.m. And the fraternity boys used to come down and practice with us. I can remember when sometimes if Lawrence High had something going on at that time over there, we'd have to go to North Lawrence Woodlawn School and practice.

MR. BARNES: The team was about half the size of what it is now, at Cordley or Woodlawn.

"Nall coached the team until 1936. By that time, the Promoters were in Kansas City, Missouri, with the Athletic Association. They were co-champions of the league that year. The Promoters would do the same in 1938 and 1940. In 1940 they were sole league champions. In 1946 Jesse Newman's nephew, Verner Newman III, began playing for the Promoters. By then, G.O. "Doc" Watson, a white journalism and social studies teacher and football coach, coached the team. He was also president of the conference in the beginning of 1945."

And then most of the rest of what I had to say, there's only one other thing, Jesse always said that they won the league, and they had a trophy. It was the only trophy the Promoters ever won, and he said they used to show it old Liberty Memorial High School. I never saw it. And he thought when they moved to the new high school, it might have went with it. And so I went up there and talked to the principal--not this one, the one before the one they have now. And he said, "There was a lot of stuff still in the basement that came from Central Junior High School and they never had uncrated it." He was going to go down and go through all of it, and he was going to have a museum built and put it in the lobby at Lawrence High School. He left without that being accomplished. And I went there about three months ago when they were giving out the football scholarships, and I had a nephew that was getting one. And I mentioned it to the football coach and one of the administrators, and they had never heard of the Promoters. This to-date football coach (laughter) and administrator. And, again, they promised they were going to do something about it, going to look into it, and they wanted to talk to me and some others and so forth. I don't think that it's going to happen though.

And the other thing that really disappointed me is that the black kids today and in past few years, they'd never heard of the Promoters. They have no idea who we were. And they really don't care anymore. They act like they don't understand that kind of thing like what we went through. So that's I wanted to get this set up and show, put our books back out there with the pictures in it and so forth.

MR. MONROE: You can put that on one of our panels. The history of the Promoters on one of our black oral history panels. Weren't we co-champions also, the Missouri Valley co-champions in 1949 when Atchison beat us? That was our last year. That was our last year. I think we was co-champions that year.

MR. BARNES: 1949.

MR. MONROE: But we played a championship up in Atchison, and Atchison beat us.

MR. MONROE: But we played a championship up in Atchison, and Atchison beat up us.

MR. BARNES: Also, we were invited by one of the history teachers about ten or twelve years ago down at Central. The class found one of our books that had been left behind (laughter). And they were going through it, and they saw the pep club and the basketball team, and they wanted to know why were these girls dressed like this in the picture? They were called the Red Peppers in the pep club, and the Red Peppers was the name that they gave them. So it was Bud and myself, the Payne girl, Alex's sister.

MR. MONROE: Mamie?

MR. BARNES: Mamie Payne was invited and a couple of others. Woody was there. And we just talked, like we're talking about. And those kids were writing, they were asking questions for over an hour. There was only one black kid in that class. Yet, they had all invited us and they were happy, and about a week later all of us got individual letters from each one of those kids, thanking us for coming up and talking to them. But, like I said, nothing's happened since. These kids right now don't know anything about us. I talked to a basketball coach from Shawnee Mission North a couple of months ago out at Free State. He was getting ready to leave with his team, and I said, "Come here. I have something I want to tell you. So I told him about how we first got started in football, and he said, "Would mind talking to my kids there?" He called the girls and boys team over in the lobby at the high school and said, "Come here. This man has something that he wants to tell you." So I told them about it. He said, "You know, I'm a history teacher and I've never heard that." He said, "As soon as I get back to Shawnee Mission, I'm going to get the principal." He said, "I'm going to wake him up and tell about this and see if we can't do something about it."

ALICE: This is why we try to do this project. Because, first of all, we want to preserve our information so that people can learn. And it's more than just our kids that need to know. Other cultures need to know. Because all of us are, although we're African Americans, mixed with something. But you'd be surprised to find how hungry other cultures are to learn about us. They don't know, and unless we continue this effort to find the information, they'll never know.

MR. MONROE: Their parents kept that away from them.

ALICE: Right.

MR. MONROE: See? The only way my kids knew was because I told them . Some of the stuff I told to my kids, it was hard for them to even believe that in this day and age. They said it made it all easier for them. Thank goodness.

MR. NEWMAN: But it's ironic that back during those days, the blacks weren't included in the athletic program. But look at the programs now, where ninety percent of your basketball teams and football teams are made up of blacks. That's because of Bear Bryant. Everybody in the world knows Bear Bryant at Alabama.

MR. MONROE: And they wasn't winning and some of the coaches told us, said, "Look, Coach, if you don't get some black guys on this team, you're not going to win any ball games."

MR. NEWMAN: Yeah, that's right.

MR. MONROE: And that's why he started, he finally broke down after I don't know how long, and started recruiting some black guys on Alabama's football team, and they then came right up, almost to the top.

MR. NEWMAN: Yeah.

MR. MONROE: Immediately with those black football players. But it took a while.

MR. NEWMAN: Oh, yeah.

MR. MONROE: It took us a while to get integrated. And, now, you see so many of them out there now, it makes you wonder sometimes (laughter).

MR. MOORE: I know the State of Kansas, when I was coming up back there in the '30s, they had a statute that said any city, the population was under 15,000, they had to provide athletic sports for all races. It was like Tonganoxie. They were integrated in sports. But Lawrence High, and I remember that sign out there by the airport back in the early '30s, that said Lawrence was 14,000 something. So we were under the 15,000 (laughter). See if they'd integrated sports.

But they weren't. They weren't going by it. And now they'll tell you, "Really it was actually 15,000 (laughter)." I remember that sign out there said 14,000 something. If they had complied with the law, they would have integrated sports back in the '30s, but they didn't.

I think that maybe we can get some of these pictures scanned and this stuff that Verner has here, and we can make a panel on some of the black history of Lawrence, Lawrence High School. And it's really interesting, and some of the stuff, that he's got it right there would really be interesting to put on our tape.

AMBER: I know that you talked about, a little bit about Lawrence and how it was segregated and all. But how did the town of Lawrence at that time receive you? What was it like for you guys as Promoters, as a basketball team, how did they react?

MR. MONROE: We grew up with it, so there was no what you might call a big deal back then because we knew that we couldn't go here, we knew we couldn't go there, to eat and things like that.

It was back up there in Topeka. I played on two state championship basket teams and Memorial. And the Hornets. So this one white guy, named Leech, said, " Les, how would you like to play with us?" And at that time it was Gold Pants. And, because the Hornets at the time was an all-black team and it had began to slip, and I just decided that it was time for me, for a change. So I told him, Leech, I said, "Yeah, I'll play if you let me bring my friend with me, Joe Douglas with me." And he said, "Okay." So me and Joe went over to the Gold Pants and, from then on, the people would be coming down there to the park to see us play, Hornets, and they was, the blacks up there. They would really knock Joe and I down.

So, anyway, we kept playing, but we'd win. And we kept on, and they'd always play with the Hornets. And it ended up, after I'd turned all the things around and everything, they still had it back then. But if finally disintegrated.

MR. BARNES: Yeah, they disintegrated.

MR. MOORE: But I was fortunate enough to be on seventeen state championships past this team. And was voted into the Hall of Fame. Outsanding!

!ALICE: What's the name of the Hall of Fame that you were voted in?

MR. MOORE: The Kansas Hall of Fame.

ALICE: The Kansas Hall of Fame?

MR. MOORE: And Associated Bureau Soft Ball Association. I went down to Wichita and was voted into the Hall of Fame. Joe Douglas and I in eight years. I don't know whether June Brown was in there or not. Mike Simpson was in there. But it really panned out. But now there's no teams at all (laughter). It's like no teams at all now. Sort of in the years it dissipated.

MR. NEWMAN: Yeah, the slow pitch was taken away.

MR. MONROE: And in the military you had to be forty years old to even play slow pitch. But we even played slow pitch at eighteen years old, or twelve years old. I don't know whether I've said enough, but we had a lot of fun. We had a lot of fun playing with our Negro teams and everything. But things like that never would have happened if it wouldn't have been for any us. He'd have never been in the Hall of Fame if it wouldn't have changed. But it changed and when it did, it opened a lot of doors for a lot of things. But I just had a blast playing back then (laughter) myself. I mean fun. Man, it was a lot of fun.

AMBER: Well, now let me ask this question. You guys referred to the Red Peppers?

MR. NEWMAN: That was the pep club. That was the pep club.The girls.

AMBER: The girls! What happened to them in the '50s when you guys became integrated? When the basketball team integrated?

MR. BARNES: As far as I know that's the same thing that... They wanted to be the football queens (laughter).

AMBER: I don't think that it was open for them to be

MR. BARNES: Cheerleaders.

AMBER: Right.

MR. BARNES: I don't know. I wasn't here, so I don't know.

ALICE: Part of what happened was that the high school came up with a program that they had to allow so many blacks to be cheerleaders and, and, uh, the leaders. They could be in pep club, but to be the cheerleaders. And then in the later years, the same thing that helped them bit them, because they said, "Well, that's segregation." When you're setting aside so many numbers. So I don't know what they're doing now But they fought to get it so that everybody had to apply and everybody was decided on rather than have the black cheerleaders. And we tried to fight for that to say, "No, we're not trying to separate, but they don't have the opportunity. There are so many white population that go out and they won't have the chance." So I don't know what happened.

MR. MONROE: Who was the first black cheerleader? She got killed. Right? She got killed coming back from Ottawa?

MR. BARNES: She was in junior high. That was Mae Hurst. She wasn't a Lawrence High cheerleader?

ALICE: No, she was in junior high when she died.

MR. MONROE: At least it was saying it was integrated at the junior high for cheerleaders.

ALICE: Right, right!

MR. MONROE: So it must have been out of one my teams integrated in high school.

MR. BARNES: I got a daughter that was a cheerleader at Lawrence High.

MR. MONROE: So did I. I had a daughter that was a cheerleader at Lawrence High.

ALICE: But I think that during the time they were, that was when they had a certain percent. They'd set aside so many spots that black cheerleaders could have.

And then they tried to do away with that. But I don't know what it is now.

MR. BARNES: And they had two queens. I think Rev. Barbee's daughter was one of the first ones that was a queen.

ALICE: Yes, I think so.

MR. BARNES: And like I said, that was one of things that went around, it was who your daddy was (laughter). A position.

AMBER: So who came up with this name Promoters? Why the name?

MR. MONROE: We don't even know when it started, so we don't know or have any idea who named it.

MR. BARNES: It was started in 1926 (laughter).

AMBER: It just came up in 1926 as the Promoters?

MR. MONROE: Yeah, it was before that I'm sure, but I don't know who came up with it. I think maybe they said, "Well, look, we got to promote something out there." That's how things do happen. "We've got to promote something, so why don't we call them Promoters?"

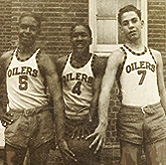

MR. NEWMAN: I didn't know about them uniforms that Jesse's talking about that that guy, Nall, bought for them, the uniforms. The uniforms we had, had Oilers all across them.

MR. BARNES: The Oilers. They were a pretty color.

AMBER: Oilers?

MR. NEWMAN: Oilers.

MR. MOORE: Well, the reason you had Oilers, the reason you had Oilers because we wanted some uniforms and Mr. Woody bought these and he give them to us out there, and they started to calling us the Promoters, started calling us Oilers. We were still the Promoters, but we had Oilers on our uniforms.

MR. NEWMAN: They were a pretty color. They was gold and white.

They were pretty, but they had Oilers on the front of them.

ALICE: Maybe he got them cheaper some place that he got a deal on them.

MR. NEWMAN: I think somebody gave them to him probably.

AMBER: Is this Mr. Woody the one who used to work out at Hallmark?

MR. NEWMAN: His daddy did.

ALICE: The one the park's named after.

MR. NEWMAN: He was a great man and they named parks after him.

MR. MONROE: There's still now what they call the Toy Bowl, that's because of him too.

MR. NEWMAN: I didn't know that.

MR. MONROE: They used to present the trophy after his dad and everything passed, Billy would present the trophy over the Toy Bowls.

MR. MONROE: Chuck knows all about that (laughter).

ALICE: Because he was one of the coaches.

MR. NEWMAN: I didn't know that.

ALICE: Still is the coach.

MR. NEWMAN: What's y'all's game plan, ice, scotch and beer?

MR. BARNES: I drank scotch and beer and everything, and I didn't have time to (inaudible).

MR. NEWMAN: Football coach. Over thirty something years now.

MR. MONROE: All you members here, that's Robert Watson. Remember when he was here?

ALICE: Oh, yeah, the saxophone player.

AMBER: Yes. The older one or the son?

MR. MONROE: This is him.

AMBER: Oh, my gosh!

MR. NEWMAN: He put me in my place.

MR. MOORE: The older one?

MR. NEWMAN: The older one.

AMBER: There's the father and then there's his son, and they look so much alike.

MR. MONROE: Why, his son is a music director at UMKC.

MR. BARNES: His son got a crew.

MR. NEWMAN: I haven't seen Robert in so long, I probably wouldn't recognize him.

MR. MONROE: He hadn't changed one bit. Just like you Newmans haven't changed one bit. Robert hasn't changed one bit.

AMBER: Which one is you?

MR. BARNES: We had a guy in legislature from Wyandotte County, his name was Robert Watson, and he looked just like them. And I thought it was Robert's son when he first came up there to Topeka. He said he gets that all the time. He lives in Wyandotte County.

MR. MONROE: Well, you wouldn't be surprised, he said he did have six sons.

MR. BARNES: But they didn't have any girls, did they?

MR. MONROE: No girls, just six boys. But the strangest thing, he used to go with my sister and they never ended up getting together. And I'll be darn, Robert got married, he had six boys, and my sister got married and she had six boys. I just often wondered, if they'd have got married, if they'd have had six boys (laughter).

ALICE: Maybe they'd have had twelve.

MR. NEWMAN: They'd have had twelve.

AMBER: Is there is anything else?

MR. NEWMAN: But track was always integrated.

AMBER: Track was always integrated?

MR. MONROE: Yes. It was always integrated.

MR. NEWMAN: You didn't touch nobody in that game (laughter).

MR. NEWMAN: 1944. .

MR. MONROE: And we had some good ones too.

AMBER: The year I was born.

MR. NEWMAN: You didn't touch nobody in that game.

MR. MONROE: Look a there. I was looking at that (laughter). I figure it had to be yours, it's way too old for me.

MR. NEWMAN: I called my niece to see if her mother had any of those old books, high school books. And she said when they moved, when she moved and everything, said everything was discarded.

ALICE: Oh, my!

MR. NEWMAN: But said if she runs into one, she'd let me know. But her and Bill, they graduated from Liberty Memorial High School together. Not Lawrence High, but Liberty Memorial.

MR. MONROE: Liberty Memorial High School.

MR. NEWMAN: Uh-huh.

ALICE: Well, I'm going to check with the high school and see if they do have, because they keep old copies sometimes. Not every year do they have one.

MR. MONROE: Wouldn't that be in their archives there? The Red and Blacks?

ALICE: Whenever I've gotten them before, they had extras, so I bought one for my brother because his had been stolen or something. They didn't have extras for every year, but they had extras and they keep them as an archival thing. I'll have to see if they had one for 1938, because I think that's the year that's on that book is thirty eight. But it's a great big book. It's not a small book like we had yearbooks.

MR. NEWMAN: I've got my junior high books.

MR. BARNES: I've got mine.

MR. NEWMAN: The books cost too much when I was going to high school, so my money was limited.

MR. BARNES: I got three of those, '47, '48 and '49.

MR. NEWMAN: Just one in our whole family.

ALICE: Right.

MR. NEWMAN: Because things were so expensive.

ALICE: You could only afford one.

MR. NEWMAN: I couldn't buy one.

ALICE: We are about to wind this up. I'll tell you what the next step is.

MR. NEWMAN: That's the ninth-grade team. Freshman team. Ninth grade. All solid purple.

AMBER: Does anybody want to add anything before we shut the tape off?

ALICE: Just a comment or whatever you want to say?

MR. NEWMAN: You're talking about, like I said, that guy that played at Lawrence High. They took a lot of things from Liberty Memorial out to Lawrence High, and it's supposed to be in the basement. If you want somebody to check and see if there's any books there.

ALICE: I'm going to. I'm going to pull some strings and see if I got any power. I'm going to pull some strings and see if I can find out.

MR. MONROE: That director, you know him real well, but I don't know if it will do any good to talk to him or not. Commons.

ALICE: Ron? Ron Commons?

MR. NEWMAN: Oh, you ain't talking about Commons. That racist (laughter)!

ALICE: Yeah? Anyway, I'll let everybody know. Because what I'd like to do is...

MR. MONROE: Yeah, he is the (eight ball?). If you talk to Darrell, I might be able to get something out of him.